For Jason Fifield, an associate at Ankrom Moisan Architects in Portland, what makes a building ugly “is when the design isn’t generated by real reasons but rather by arbitrariness, just for the sake of creating an image.”

To compile our list of the world’s ugliest structures, we consulted with architects and design experts as well as the general public. Pretty much everybody had something to say. For instance, there aren’t many admirers of the spherical houses on long pole “stems” planted, like so many mushrooms, in the Netherlands. (The architect was given free rein courtesy of a Dutch subsidy for experimental housing.) Then there’s the midwestern corporate headquarters that takes the form of a huge picnic basket. Sure, it’s funny from the outside, but probably not for the employees of Longaberger, in Newark, OH, who have to go work in a hamper every day.

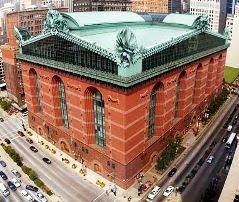

1. Harold Washington Library,Chicago

If buildings came with footnotes, this one, named for a beloved former mayor who deserved better, would have pages worth of citations. Neoclassical references collide with a glass-and-steel Mannerist roof; throw in some red brick, granite, and aluminum—and a bad sense of scale—and you’ve got way too much architecture class for one day.

The Ugly Truth: Opened in 1991 and designed by the firm Hammond, Beeby, and Babka, the Chicago public library has a helter-skelter application of motifs and styles that’s “locked in the postmodern era,” says Peter Koliopoulos of Circle West Architects in Scottsdale, Ariz.

2.Longaberger Home Office,Newark, Ohio

If you worked here, you’d be conducting business in a 9,000-ton copy of a woven-wood basket. Its stucco-over-steel construction was an award-winning feat, apparently; the synthetic plaster received a prize. But it’s as if, in 1997, a giant-size Little Red Riding Hood set down her seven-story hamper on a flat section of Ohio.

The Ugly Truth: True, the company purveys handcrafted baskets. And founder Dave Longaberger’s dream headquarters was a replica of his favorite basket. But hey, Crate & Barrel employees don’t schedule meetings in a 10-story sofa.

3. The Ideal Palace,Hauterives, France

Cinderella’s dream digs it’s not, but Le Palais Idéal does bring to mind a fairy tale — the kind one might have visions of after dropping acid. Gargoyles peer out at grottoes with Hindu temples, and tiny mosque-motifs adorn squiggly stone pillars.

The Ugly Truth: In the mid-1800s, Ferdinand Cheval tripped over a stone while delivering mail and was seized with inspiration—his life’s work would be to build a stone château. Over the next three decades, he marked stones while covering his route, returning in the evening with a wheelbarrow to collect them.

4. The Portland Building,Portland, Ore.

Let’s break out the government-building checklist. Small, boring windows? Check. Humdrum off-white masonry? Yes. Terracotta pilasters and shiny blue glass? That, too. The first three levels of the squat, 15-story municipal-services structure are covered in dark green tiles, adding to the bewildering gaudy-meets-tedious tone.

The Ugly Truth: Michael Graves won a competition to design the building in 1982. Postmodernism was all the rage in the ’80s, which explains the randomly-stuck-on historical motifs. “Many buildings from that decade look fake,” says architect Stephen R. Connors, who has his own firm in Warwick, NY.

5. Bolwoningen Houses,Hertogenbosch, Netherlands

If Lewis Carroll’s Alice wandered into a 1960s sci-fi flick, she might have come across something like these bulbous houses. The residents live inside bizarre-looking bubbles (small ones, at 18 feet across) with UFO-like windows.

The Ugly Truth: In the late 1970s, the Dutch government offered subsidies for experimental housing, and the architect—one Dries Kreijkamp—certainly complied with the directive. The 50 bolwoningen (bol = sphere, woningen = houses) sprouted up in a city that seems to infect artists with a fantastical streak; it’s the hometown of Hieronymus Bosch, the 15th-century painter known for his half-dream, half-nightmare-like renderings.